Chez les Filles

October - December 2019, Peter Kirk Travel Fund

An exploration of regional French ceramics, tradition, community and skill.

By visiting historical and active pottery sites in France, I hoped to explore the link between clay and community, discover how craft is being taught today, in what capacity history and technique play a role within this and whether skill is being passed on. I was eager to look at the lifestyle surrounding ceramics and whether it is resistant to society’s advances, and explore whether ceramic art is innovative.

[extracts from full report]

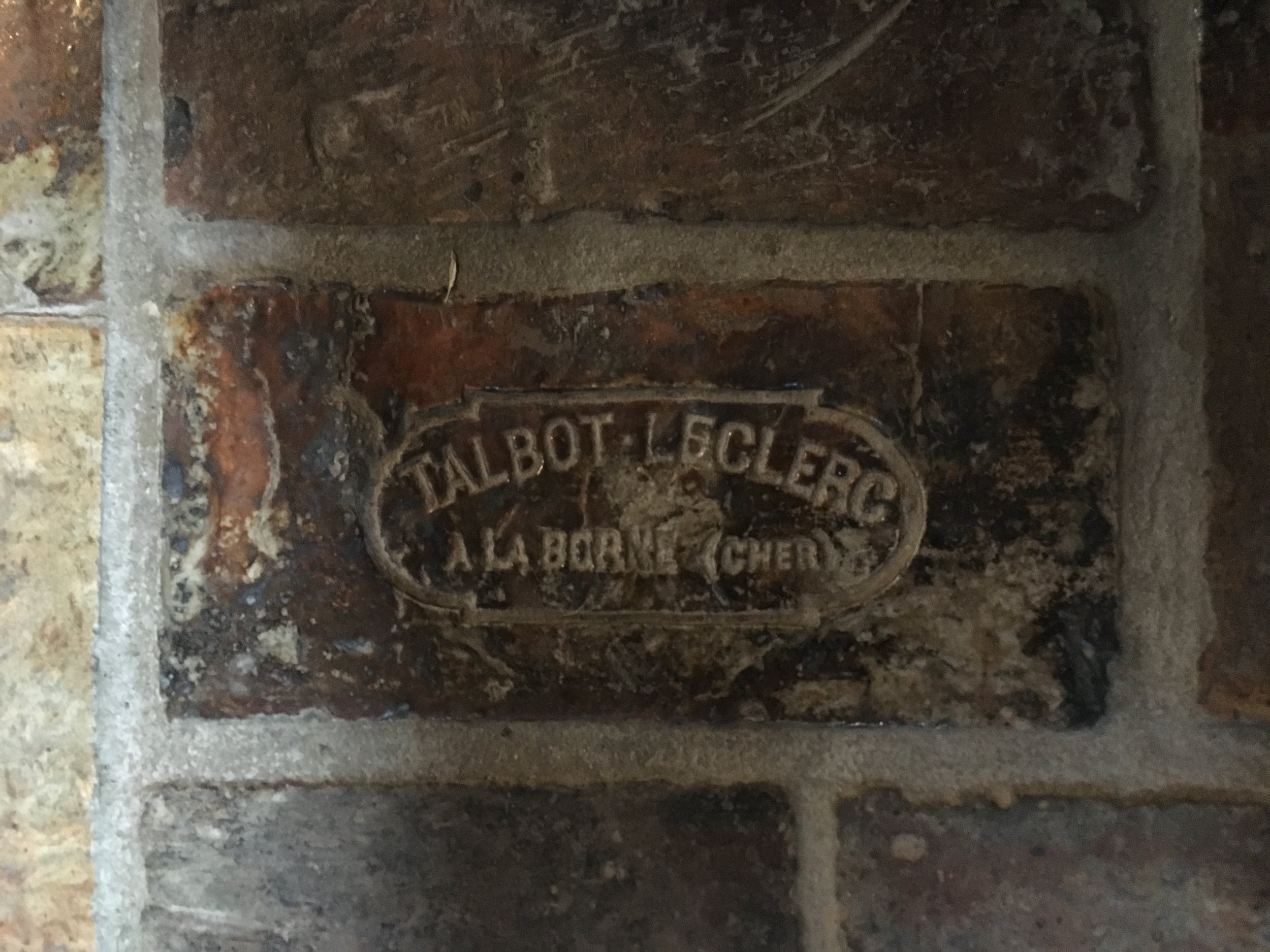

La Borne

Potters who worked in La Borne have historically been artisans. The production of ceramics used to be communal, roles were specialised to maximise efficiency. This is much like Jingdezhen today, where labour is still divided between mold-makers, glazers, throwers, down to the humble porter. In China, I was scorned for trying to master every technique myself. Nowadays, the Western notion of creativity inclines toward individual, artistic production, unlike the more persistent collective attitude of the East. This is true also in La Borne, where contemporary potters compete against one another.

The pioneering groups [who re-established the village after the war] had been young, typically under thirty. Those who now remain are elderly, and although potters are still arriving, they are not young either. This throws into jeopardy the future of the village. Who will continue its traditions and skills that have so painstakingly been preserved? As I explored, I felt this could become a historical site within a couple of decades, much like the old porcelain factory in Jingdezhen, where hired potters play out the roles of old artisans for visitors to observe. La Borne is much less attractive to the young now – it has essentially been regenerated. House prices have risen, and there are few new paths for a new generation of potters to forge. The traditional life lingers strongly and feels disconnected from contemporary living and the new market for ceramics that is pervasive through technology. The question of how to continue is unclear.

It is clear that wood-firing here is more than a process: it is direct, consuming, elemental, vigorous – far beyond the significance of the flick of the switch of an electric kiln. It seems that the promise of this life, so contrary to increasingly automated life elsewhere, is what has drawn many of these potters to La Borne. I have often thought of pottery as a kind of resistance, and here I see it in action, to the extreme.

A crowd gathered at the opening of Claire Linard’s kiln, (daughter of Jean), sheltering closely from the rain under a tin roof. We peered as the pots were passed between hands and made it onto the table, slow and cerebral. Questions were shouted about the effects and materials and answered humorously. An elderly and rugged potter with roll-up hanging from lips, flat cap shoved over dishevelled hair, dropped the most elegant of teapots. Collective intake of breath from the audience. It was grabbed from catastrophe, and we sighed in unison, then applauded and rippled with laughter. At the opening of Maya Micenmacher’s kiln, we lined up diligently in front of the kiln where saggars (ceramic cases used to protect wares during firing) were broken open with a chisel, and carried warm pots to a long table, where they were snatched up by greedy hands. The records of all the previous firings were displayed in a thick volume. There was old mismatched furniture on sandy rugs, faded patches on the seats of chairs – the ghosts of those who have monitored the kiln late into the night.

Jean Linard said ‘building communally is a kind of religion.’ The process and lifestyle of wood-firing within La Borne lends itself exceptionally to establishing a community. It is high-energy and relies on a skilful team. This has changed since the production of pots has become individualised, but the very act of kiln-firing has become a form of celebration, it brings people together with this specified interest. I felt I had entered into a subculture distinct and unknown to the outside world.

Sèvres & Limoges

Sèvres is now brilliantly committed to linking the manufacturer’s past prestige to contemporary projects. Johan Creten was the first artist-in-residence, from 2003-7. He made use of the traditional techniques whilst being incredibly ambitious and pushing his sculptures to the limits of clay. This feels like an essential extension of the manufactory’s traditional output which are proudly displayed in grand and regal galleries. Gargantuan pots to glorify historical events, exquisite luxury tableware, ornaments. Gradually these traditional forms have succumbed to more contemporary artistic experiments, becoming the fabric for intervention and rejuvenation and put to sculptural and conceptual use.

*

In the Musée National Adrien Dubouché

The level of dedication to the display and history of ceramics reflects its importance within our heritage, positing the material as a crucial part of French, European and global socio-political history. The detailed and meticulous permanent display spanning many centuries and countries is housed alongside temporary galleries showing current and ground-breaking work. Nothing to my knowledge compares to this in the UK, other than perhaps the ceramics gallery in the V&A. All this within a provincial town in France – determined to safeguard its history and sustain it through providing public resources.

Cliousclat

Inside the long narrow workshop three potters were at work. Down the left side were the customary drying racks, wooden brackets stretching out from the wall with boards balanced and replete with bowls, dishes, plates and drying slowly. One guy was mixing huge buckets of engobe, another sat at his bench and prepared to throw. A woman carefully trailed slip designs over the leather-hard wares. She was welcoming, recounted the pottery’s history and invited me to sit by the stove to stay warm and write.

I watched the thrower take long sausages of clay from the pugmill and masterly mark out identical sized lumps with his knife so he could begin throwing bowls. He comes to the workshop a handful of days every few months, and wheel-throws all the pottery’s wares within that time. His skill was impressive, he worked at speed, tossing bowl after bowl onto the long board placed before him. He told me how much he loves this workshop, how traditional potteries such as this one are increasingly rare because people want autonomy, to work on their own travail. Again, I was struck by the general move away from collectivism and collaboration, the search for true individual creation which seems to reflect how individualist our society has become, down to taste for objects and their creation.